Six incredible space missions to look forward to in 2021

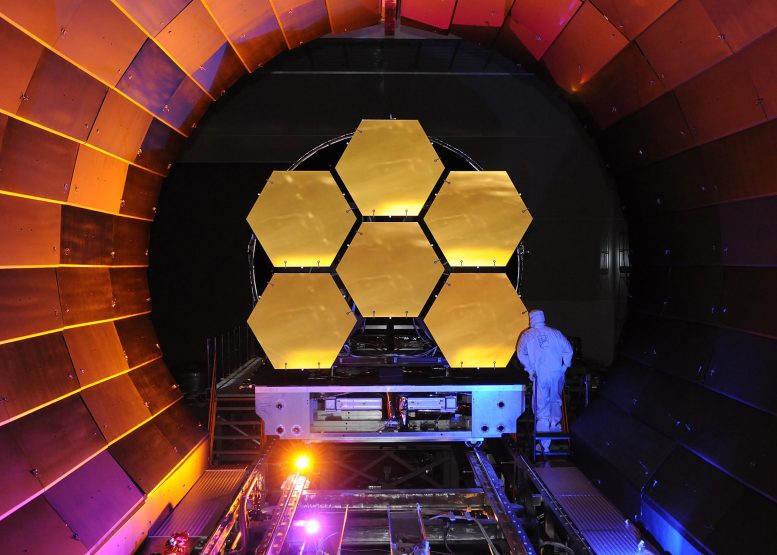

NASA’s James Webb Telescope mirror undergoes cooling test. Paul Aerospace / Flickr, CC BY-SA

Space exploration has made several notable achievements in 2020 though Covid-19 Epidemic, including commercial human spaceflight and asteroid sample return to Earth.

Next year is shaping up to be interesting. Here are some things to watch out for.

Artemis 1

Artemis 1 is the maiden flight NASALed by Artemis’ international program to return astronauts to the moon by 2024. This will consist of an unmanned Orion spacecraft that will be sent on a three-week trip around the moon. Information technology will reach a maximum distance of 450,000 kilometers from Earth – the farthest distance in space any spacecraft capable of carrying humans.

Artemis 1 will be launched into Earth orbit on NASA’s first space launch system, which will be the most powerful rocket in operation. From Earth’s orbit, the Orion will be propelled into a different path toward the Moon by the missile’s temporary cooled propulsion stage. The Orion capsule will then travel to the moon under energy provided by the Service Module provided by the European Space Agency (ESA).

The mission will provide engineers returning to Earth an opportunity to assess the spacecraft’s performance in deep space and serve as an introduction Crew later Lunar missions. Artemis 1 is currently slated to launch in late 2021.

Mars missions

In february, Mars A fleet of guests will receive ground robots from several countries. The UAE’s Al-Amal (Hope) rover is the first interplanetary mission in the Arab world. It is set to reach Mars orbit on February 9, when it will spend two years observing the Martian weather and the disappearance of the atmosphere.

Tianwen 1 of the China National Space Administration will arrive in two weeks after the Hope Project, consisting of an orbiter and a surface craft. The spacecraft will enter Mars orbit for several months before deploying the spacecraft to the surface. If it succeeds, then China will become the third country to land on Mars. The mission has several objectives, including mapping the mineralogical composition of the surface and searching for groundwater deposits.

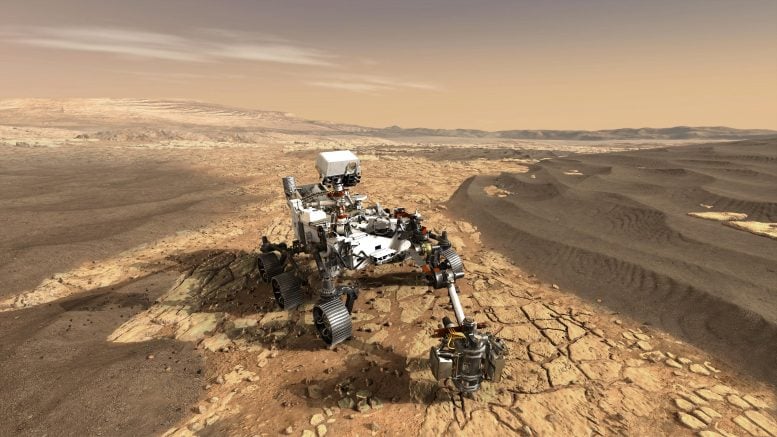

NASA’s Perseverance spacecraft, shown in this technical rendering, will land at Jezero Crater in Mars in February 2021 and begin collecting soil samples shortly thereafter. Scientists are now concerned that the acidic fluids, once they reach Mars, may have destroyed evidence of life in the mud. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Tenacity vehicle will land at Jezero Crater on February 18th and look for any signs of ancient life that might have been preserved in the mud deposits there. Importantly, it will also store a cache of Mars samples on board as the first part of a very ambitious international program to bring Mars samples back to Earth.

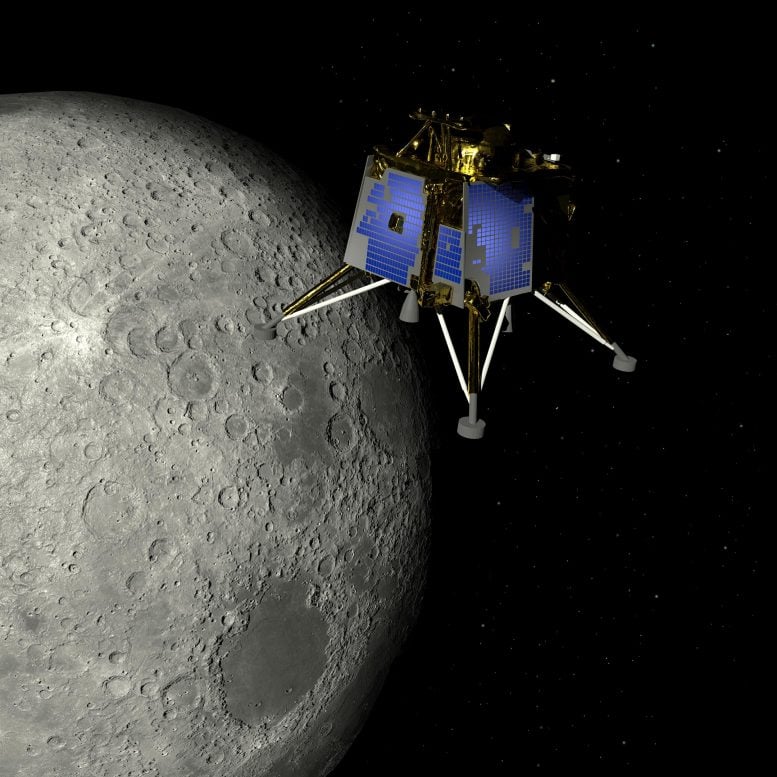

Chandrayaan-3

In March 2021, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) plans to launch its third lunar mission: Chandrayaan-3. Chandrayaan-1 was launched in 2008 and was one of the first major missions of the Indian space program. The mission consisted of a probe and a penetrating surface probe, and it was one of the first missions to confirm evidence of the existence of moon water.

Unfortunately, he lost contact with the satellite after less than a year. Unfortunately, there has been a similar incident with its successor, Chandrayaan-2, which consists of an orbiter and lander (Vikram) and a lunar module (Prajian).

Chandrayaan-3 was announced a few months later. It will consist of lander and rover only, as the former orbiter is still operational and providing data.

If all goes well, the Chandrayaan-3 rover will land in the Aitken Basin of the Moon’s South Pole. It is of particular interest as it is believed to host numerous groundwater ice deposits – a vital component of any sustainable lunar habitat in the future.

James Webb Space Telescope

The James Webb Space Telescope is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, but it had a rocky path to launch. Initially planned to launch the Webb Telescope in 2007, it was delayed some 14 years and cost nearly US $ 10 billion (£ 7.4 billion) after apparent underestimation and overruns similar to those experienced by Hubble.

While Hubble provided some stunning views of the universe in the region of visible light and ultraviolet rays, Webb plans to focus observations in the infrared wavelength range. The reason for this is that when observing truly distant objects, there are likely to be gas clouds in the way.

NGC 2775 as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: ESA / Hubble & NASA, J. Lee, and the PHANGS-HST Team. Acknowledgments: Judy Schmidt (Gikzela)

Gas clouds block these very small wavelengths of light, such as X-rays and ultraviolet rays, while longer wavelengths such as infrared, microwave, and radio can pass more easily. So by observing at these longer wavelengths, we should see more of the universe.

Webb also has a much larger 6.5-meter mirror compared to Hubble’s 2.4-meter mirror – essential for improving image resolution and seeing fine details.

Webb’s primary mission is to look at light from galaxies at the edge of the universe that can tell us about how stars, galaxies, and early planetary systems formed. This will likely include some information about the origin of life as well, as Webb plans to shoot Exoplanet Ambiance in high detail, in search of the building blocks of life. Are they on other planets, and if so, how did they get there?

We’re also likely to come across some amazing images similar to those produced by Hubble. Webb is currently slated to launch an Ariane 5 missile on October 31.

Written by Ian Whitaker, Senior Lecturer in Physics, Nottingham Trent University and Gareth Dorian, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Space Sciences, University of Birmingham.

Originally published on Conversation.

“Reader. Travel maven. Student. Passionate tv junkie. Internet ninja. Twitter advocate. Web nerd. Bacon buff.”