Apple's memory loss in the face of competition

In the systems-on-chip sector, competition is starting to wake up and the lead that Apple occupied when it launched the M1 chips in 2020 is diminishing. This is what we explained in a recently published analysis. But there's a second area where Apple is also missing out: random access memory (RAM). Rest assured, this isn't a new article about the fact that Macs have only arrived with 8GB of RAM since 2016.

RAM, some quick basics

RAM (Random Access Memory, l RAM) is the working memory of the computer in the broad sense. It contains all the data processed by the processor (CPU) and is defined by several properties. Typically you will find technology type, frequency, perhaps bandwidth and carrier, and rarely latency.

Let's start with the first two related features: Currently, you can buy DDR4 (4th generation DDR) or DDR5 memory, which is twice as fast, or more precisely, transmits twice the data at the same frequency.

Frequency is often plugged into megahertz, but that's a misnomer: it's equivalent to SDRAM. This memory from the 90s used to transfer 1 bit per cycle, and was replaced by DDR which transferred 2, DDR2 which transferred 4, etc. DDR4 memory is up to 16-bit, DDR5 memory is up to 32-bit. By convention, manufacturers typically advertise the equivalent of SDRAM or perhaps mega transfers per second (MT/s): DDR4-3200 (sometimes referred to as 3200MHz or 3200MHz, so) running at 200MHz internally but transferring As much data as 3200MHz SDRAM. At the same frequency (200MHz), you also have DDR3-1600 or DDR5-6400. Small resolution, there are two frequencies: an internal frequency (200 MHz in the example) and an external frequency, which is the frequency of the component connected to the motherboard. The latter is clocked at 1,600MHz with DDR4-3200, for example, or 800MHz with DDR3-1600 and 3,200MHz with DDR5-6400.

Let's move on to bandwidth and bus, which are two related values. Since the end of the 1990s, the units have operated on a 64-bit bus and transmitted 64 bits per cycle. DDR4-3200, again, can be referred to as PC4-25600. To get this value, you must multiply the bus width by the SDRAM equivalent frequency (i.e. 3,200 x 64) and then divide the result by 8 to arrive at the result in MB/s, i.e. 25,600 MB/s (or multiply the frequency by 8 directly, which is simpler). At the same frequency, DDR5-6400 is PC5-51200, etc. In the majority of modern computers, RAM is either on a larger bus, as is the case with Apple, or the system operates on two or more channels. In this case, schematically, it is up to two 64-bit modules simultaneously to deliver the equivalent of a 128-bit bus (and 256-bit on four channels, etc., as you understand).

Latency finally refers to the time required to reach the cell in nanoseconds. The lower it is, the higher the performance. It depends on the frequency but also on the memory technology. It's not intuitive, but it may be less good in the modern version than in the old version for redundancy reasons. As we saw above, DDR4-3200 actually runs at 200MHz, while DDR5 is twice as fast. But the first DDR5 chips were DDR5-4800, i.e. 150MHz memory with lower latency than DDR4 but higher bandwidth. Latency is rarely reported by PC manufacturers, but is sometimes found on RAM chips with a CAS value, which is part of it: the lower it is, the higher the performance, with an effect that remains despite everything. Completely humble.

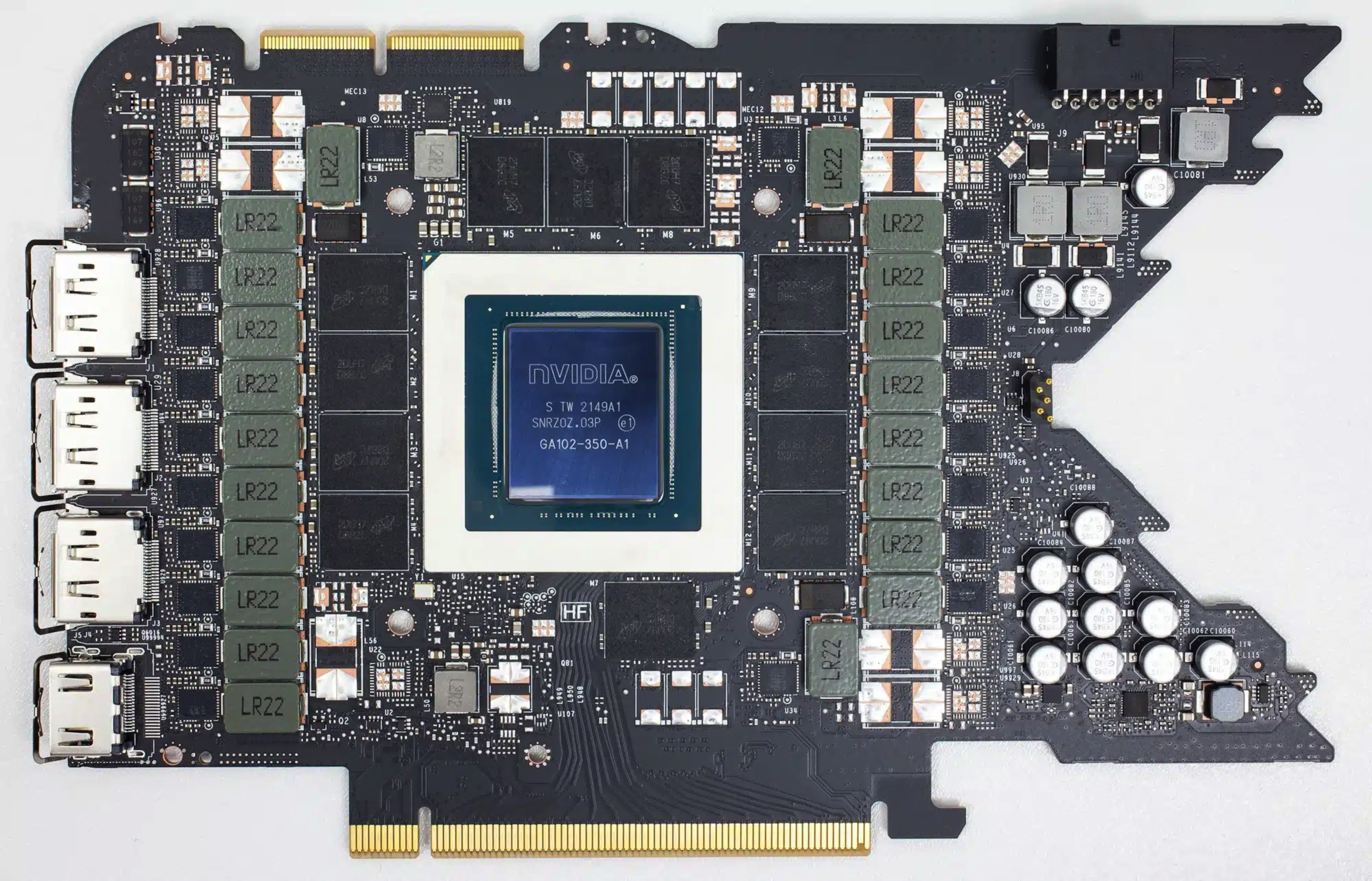

Video memory, used by GPUs, follows the same rules but with different technologies (GDDR, for example, meaning G.D.R., for example). Graph) and fairly spacious buses. At the entry level, you can get simple DDR4 on a 64-bit bus, while a gaming graphics card can integrate GDDR6 on a 384-bit bus or HBM on a 512 or 1024-bit bus. Some GPUs also share traditional RAM, for economic or practical reasons.

Finally, a point about performance: in theory, the processor should be able to access memory as quickly as possible. In practice, modern chips contain what are called caches: small areas of very fast memory placed as close to the processor as possible, where data is transferred and held so that it can be accessed more quickly. There are several levels (from the first level, L1, to the third or fourth level, L3 or L4), from the fastest (and smallest) to the slowest (and most exciting).

In use, even the fastest CPUs don't really benefit from more than 200 GB/s of bandwidth, except in very specific cases. Beyond that, gains are uncertain when they exist. For the graphics part, it's different: some tasks have huge bandwidth requirements, such as games or calculations associated with AI tasks.

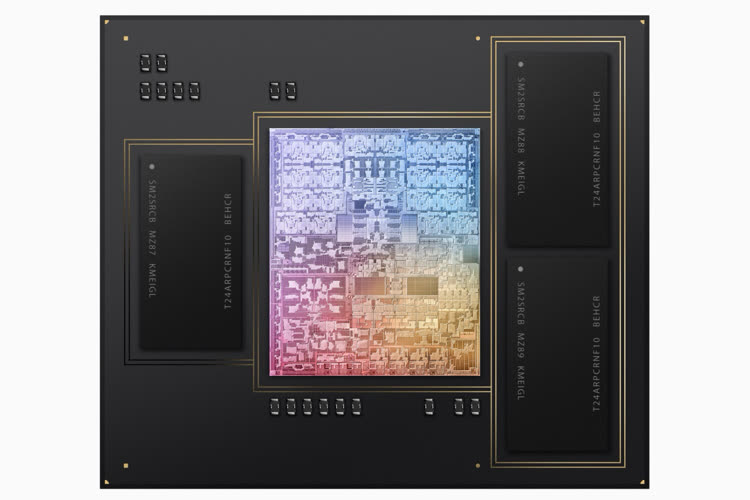

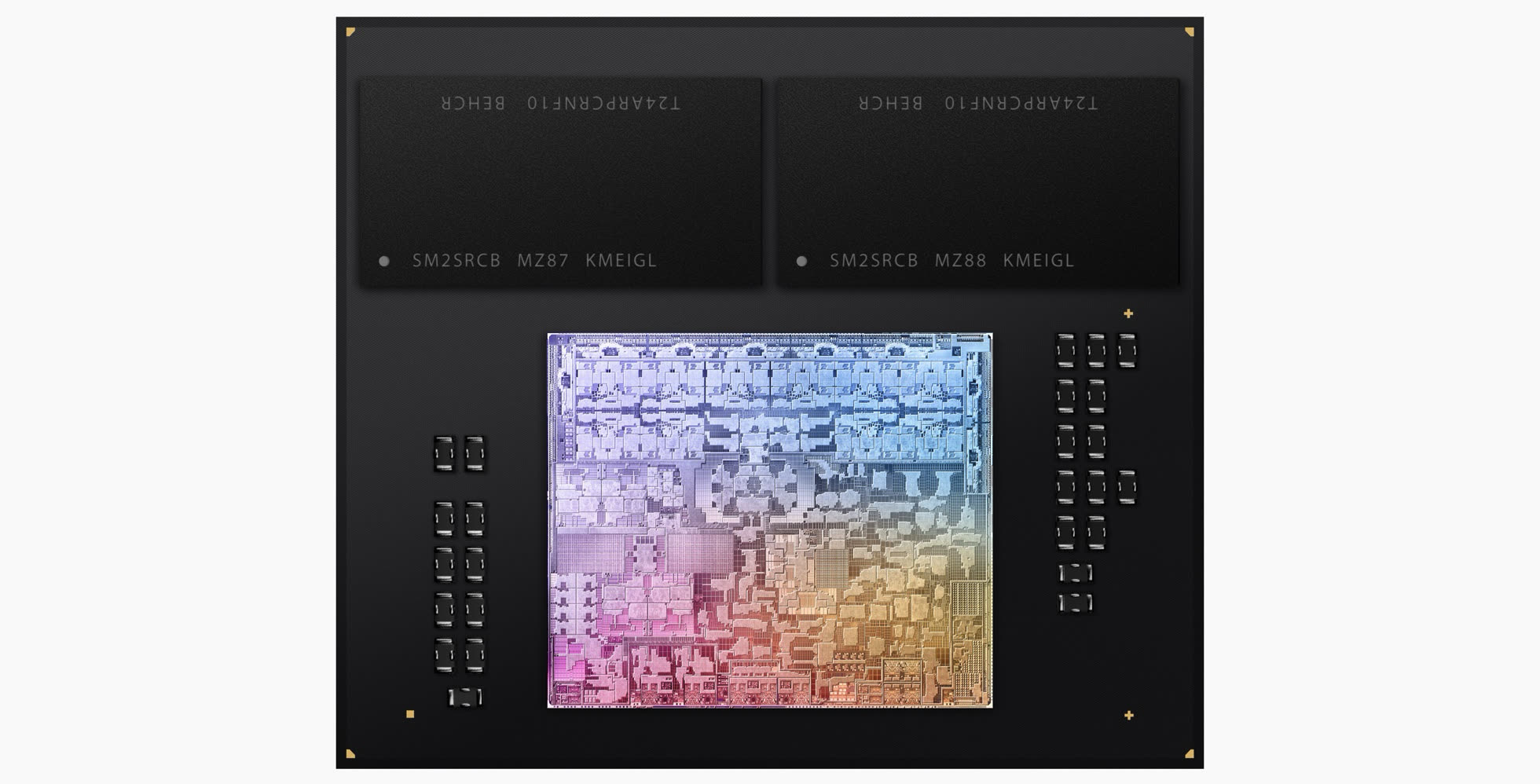

Memory management in Apple

“Incurable web evangelist. Hipster-friendly gamer. Award-winning entrepreneur. Falls down a lot.”