Free trade agreements, thieves’ corners

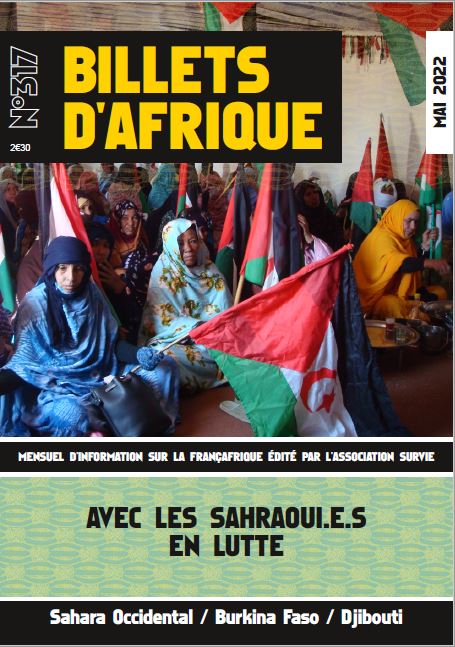

- Marie Bazin’s photo

After the Spanish colonizer withdrew from Western Sahara in 1975, Morocco invaded the territory, and the natural resources and major cities came under the kingdom’s control. Since then, the role of the Sahrawis living on these occupied territories has been limited to that of second-class citizens, with economic opportunities granted mainly to Moroccan settlers. Others live in the so-called liberated areas, controlled by the Polisario Front, the legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people, while some have to resolve to remain in refugee camps in Algeria, dependent on humanitarian aid. The United Nations was supposed to organize a referendum on self-determination in 1992, but that never happened, opening the door to a status quo that effectively supports the pillaging of the region’s wealth by Morocco and its allies.

In this context, in 1996 the European Union signed an association agreement with Morocco to create a free trade area. In 2010, a new trade agreement was signed, further liberalizing the agricultural and fishing sectors. Everything that is produced in Western Sahara is not excluded from the agreements, much to the chagrin of the local Sahrawi population who, of course, did not have the opportunity to give their opinion. From November 2012, a long legal saga began. Polisario opposes the application of this agreement to Western Sahara. Despite rulings by the European Court of Justice in favor of the Sahrawi movement, in December 2016 and February 2018, the European Parliament agreed to apply the agreement to Western Sahara. The battle now seems endless. In September 2021, European justice issues a new ruling in favor of the Polisario, but the Council of the European Union and the European Commission are quickly appealing. Meanwhile, resource looting continues and a deep free trade agreement between Morocco and the European Union remains on both sides’ cards.

“We are surprised that the European Union continues to implement the Convention in Western Sahara. […] Glihana Mohamed, vice president of the Sahrawi Group Against Looting, said in an interview with bilaterals.org [1]Free Trade Agreements website. “We consider that the European Union legitimizes the illegal occupation of Morocco, […] Whereas in the case of Palestine, […] Europeans behave differently with Palestinian products from Israeli companies.”

Political geography and trade are two sides of the same coin

These double standards undoubtedly reflect the presence of many economic and strategic interests in Western Sahara. For example, there are many French multinational companies in the region, in various business sectors. We can call it Vinci (infrastructure), Alcatel (Telecom), CMA CGM (transportation), Azura (agriculture) or Engie (seawater desalination for irrigation). The Sahara is also rich in natural resources, some of which are exploited by French companies. Optorg, through its subsidiary Tractafric, is present in the phosphate sector required for the manufacture of chemical fertilizers; Voltalia works in renewable energies; While Total has been prospecting for oil for a few years.

These cases are for France only. Other European multinationals are also well established in this region. They have powerful lobbyists at their disposal that put daily pressure on the institutions in Brussels.

Across the Atlantic, Morocco has another strong ally, the United States, with which it signed a free trade agreement in 2004. At the end of 2020, one of President Trump’s last diplomatic actions was to open a US consulate in Morocco, in Dakhla. , the economic heart of the desert region. Biden, once elected, will not question this decision.

As our Galihna Mohamed notes, Western Sahara is ultimately one of the last instances of old colonialism, interacting with neo-colonial practices, “where economic interests merge with political struggles for independence”. Multinational corporations are spearheading neo-colonialism, crossing borders and controlling governments.

Even if the Western Sahara issue is often sunk into oblivion, Julihana Mohamed and her comrades remain optimistic, seeking inspiration from the struggles in Palestine or South Africa during the apartheid era. Recently, in New Zealand, which imports desert phosphates, a small group of volunteers succeeded in bringing the matter to the New Zealand Parliament and taking legal action, after reaching out to local media and MPs. So all is not lost. “We may not win our independence soon, but we keep fighting,” he concluded.

Achille Mel Dancourt

“Organizer. Social media geek. General communicator. Bacon scholar. Proud pop culture trailblazer.”