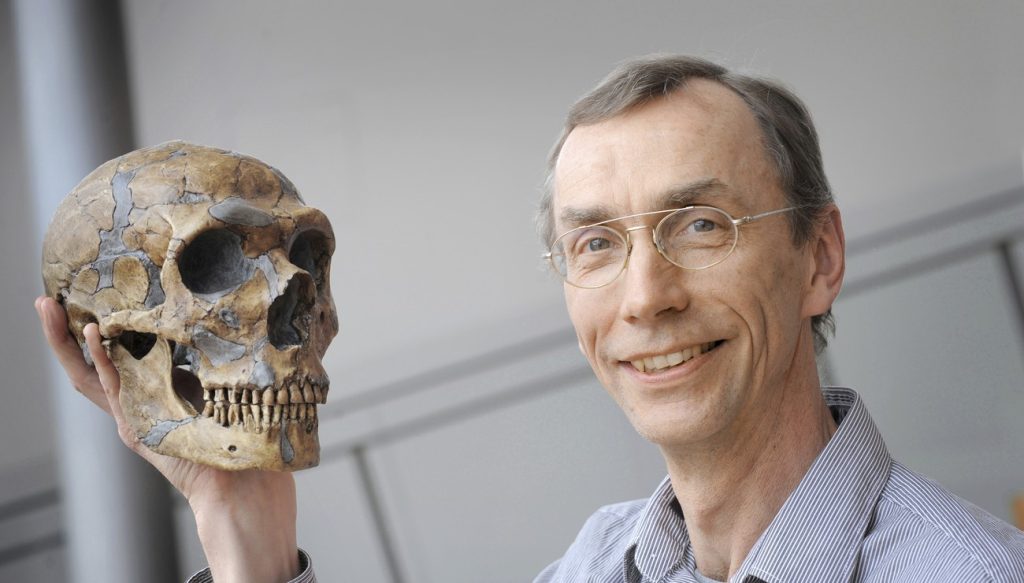

Svante Pääbo, an ancient DNA translator, receives the 2022 Nobel Prize in Medicine

The Nobel Committee just awarded Paleontologist Svante Papu Prize for Medicine and Physiology. Born on April 20, 1955 (67), he is the son of Estonian chemist Karin Papu and Swedish biochemist Sonn Bergström, for whom he shared the 1982 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for his work on prostaglandins.

Svante Pääbo is one of the pioneers, if not the founder, of paleobiology – a science aimed at recovering and studying fossil genomes – a significant contribution, which explains why he is so rewarded on his own. While receiving his doctorate in 1986 at Uppsala University, Sweden, he secretly tried to sequence the DNA of an Egyptian mummy. This is how any paleontologist learns the first lesson: fragments of ancient DNA are always drowning in an ocean of alien DNA from hundreds of thousands of scavengers and all those who have come close to the source, starting with archaeologists…

The rigorous methods he developed to reduce this contamination, and then to extract ancient DNA, are the basis of paleogenetics: they made it possible to extract enough DNA for polymerase chain reaction, providing enough readable parts to assemble the entire genome, with the help of a computer program. An amazing breakthrough, given that the human nuclear genome – found in the nuclei of cells – contains 3.2 billion nitrogen base pairs.

Far from satisfied with his critical pioneering role in the biochemistry of ancient DNA sequencing, Svante Pääbo has accompanied the rise of rapid sequencing and the development of bioinformatics methods for reconstructing ancient genomes, and has not overlooked the biological study of ancient organisms.

In 1997, he left the University of Munich where he sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of a Neanderthal (found in mitochondria), and became one of the five directors of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, then founded in Leipzig. From there, his team’s major discoveries followed.

Thus, in 2006, his team published the first part of the nuclear genome of a Neanderthal. Then, in 2010, the first nearly complete Neanderthal genome. Today, we have ten Neanderthal genomes sequenced, four of which are highly reliable. In 2010, he included the sequencing of the genetic chimera, consisting of the partial genomes of three individuals. Since then, Svante Pääbo has shown that all non-African populations typically carry between 1 and 4% of Neanderthal DNA, a range that has now decreased to between 1.5 and 2.1%. In the same year, his team discovered the genome of an unknown human form on the part of a little finger, from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Since then, paleoanthropologists have wondered which Asian fossils can be attributed to the Denisovans. Another amazing result: in 2013, his team was able to replace 16,302 nucleotides in the correct order out of the 16,500 nucleotides in the mitochondrial genome in Homo heidelbergensis (ancestor of theH. neandertalensis And the’H. sane and the Denisova man), who died more than 400,000 years ago.

However, the scientific impact of Svante Papu is most impressive above all: both his students and the paleobiologists who adopted and improved his methods multiply discoveries relating to species of human fossils, as well as discoveries of horses, mammoths and bears. Wolves, some plants. He made old-school DNA analysis.

“Organizer. Social media geek. General communicator. Bacon scholar. Proud pop culture trailblazer.”