Sensory illusions: when our brain plays tricks on us

This article is from Les Indispensables de Sciences et Avenir Issue 210, dated July/September 2022.

Straight lines that seem to curve to us, serpents that seem to spin in a still image, a voice that rises forever in treble…: Science calculates a variety of illusions, relating to all our senses, but not always explained by them. as they say, “happens in the headAnd the workings of our nervous system are still very far from being fully explained.

Let’s take an example of a particular dress that appeared on the Internet. From the light reflected by something, our brain tries to separate its color from the color of the lighting, Explains Pascal Mamasian, director of the Cognitive Systems Laboratory at École Nationale Superior. It corrects colors based on lighting assumptions.” If we see the dress in blue and black, it is because the premise of white light prevailed. On the contrary, if we see it white and gold, it is because the hypothesis of bluish lighting has prevailed.

“It is an illusion that remains, The researcher adds. If we see the blue dress today, chances are it will still be blue tomorrow. This interpretation of colors results from “unconscious reasoning,” a phenomenon that has been theorized since 1855 by German physicist and physiologist Hermann von. Helmholtz (1821-1894): Experience interferes with perception.

the dress Which has raised many questions and reactions on the Internet: is it blue and black, white and gold, or sky blue and bronze? credit: SLATE

Our nervous system learns over time how the real world works, and its interpretation mechanisms incorporate this knowledge. The dress example shows us a principle to keep in mind: our senses are not measuring instruments controlled by our conscience. “What we see, or what we think we see, is the explanation given to us by our perceptual system, The researcher adds. We are not aware of the raw information, the signals that the sensory neurons pick up.” Because between these sensors and our consciousness, many things happen that escape them, and the opportunities for illusions are manifold.

“Some of them can be explained simply by the ‘fatigue’ of certain neurons, Guillaume Masson, director of the Timone Neuroscience Institute in Marseilles, explains. This is the case of the waterfall illusion. The delusion, as early as the first century BC, was described by Lucretius in his famous treatise “From Natura Rerum”. “If, after looking at a waterfall for some time, you turn your gaze to the side, say to a stone, it seems to be moving in the opposite direction, researcher says. This phenomenon is attributed to the decreased excitability of the neurons of the visual system specialized in detecting movement from top to bottom, in the face of a constant stimulus, a mechanism It is called ‘neural adaptation’. This type of illusion simply illustrates the limits of our sensory system.…

In this optical illusion, Called cafe wall, all straight lines look distorted even though they are perfectly parallel. The effect results from their interaction with the black squares. Credit: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Like a menthol drink that makes us feel cold

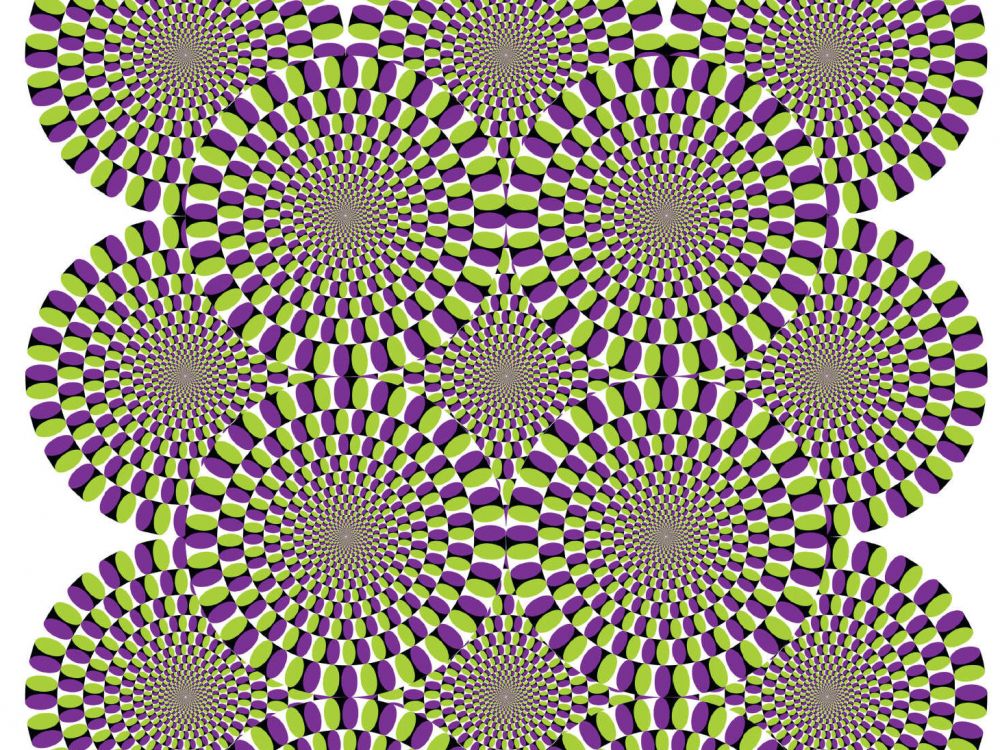

The impression of movement in front of a still image can even be perceived. The best example of this is undoubtedly this illusion called Rotating Snakes, which we owe to Japanese psychologist Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a prolific author in the field of optical illusions. These snakes generate an irrepressible sense of movement in the vicinity of the area one is staring at. It is generally believed that this phenomenon can result from a combination of small, continuous movements of the eyes and the shift between processing speeds by the sensory system of certain areas. In particular, high contrast areas will be detected faster than low contrast areas…

Some illusions find their interpretation at the beginning of our sensory circuits. Why do menthol drinks seem cooler to us than they are now? And how does the capsaicin in peppers induce this misleading sense of heat? This delusion was explained by two American researchers who were honored with the Nobel Prize in 2021. notes Laurent Perrinet, a researcher at the Timone Institute of Neurosciences.

David Julius discovered in 1997 that the TRPV1 receptor, found on the surface of some sensory neurons and known to be sensitive to capsaicin, was also a thermoreceptor. For his part, Ardem Patapoutian showed that the TRPM8 receptor, which was known to be sensitive to menthol, is also a cold receptor. In both cases, the thermosensitive circuits are somehow tricked out by molecules capable of excitation of their receptors independently of temperature.

Emojis attest to this: it doesn’t take much to “see” a face

Illusion can also result from the predictive nature of our sensory system. Our brain always tends to look for meaning in what it receives, what it sees or hears, Laurent Pyrenees explains. So much so that he can “see” a face in the form of a mountain formation on the Moon or on the surface of Mars. A phenomenon called “pareidolia”.

Note that seeing a face somewhere does not require much, as evidenced by the success of the icons. Speaking of faces, our detection mechanism seems to be… adept at shortcuts. See these upside-down photos of Margaret Thatcher or Elon Musk that we accept for what they claim to be: Upside down photos. But all you have to do is flip these images over and you’ll see that the eyes – sometimes the mouth too – are mirrored and are thus … right side up. Our visual system, having found two eyes, a nose and a mouth, decided without swinging that it saw a face, without worrying about the relative orientation of these elements.

On this inverted image For singer Adele, we don’t notice anything out of the ordinary. While flipping the image…Credits: TWITTER / TURNYOURPHONE

A category of particularly striking delusions includes not one, but two of our sensory modalities. Such is the case of the McGurk-MacDonald effect, named after two British researchers who, in 1976, placed volunteers in a state when they saw someone talking on a screen, broadcasting mixed signals. When asked what the person said, they got strange results: When the volunteers listened to a “ba” as they saw the person’s mouth forming a “ja”, they claimed to have heard… “da”. The observed effect of repeated isolated syllables has on words and even complete sentences. “It is an illusion that works every time, which is rare, Pascal Mamasyan confirms. Faced with a conflict between hearing and sight, our nervous system must decide.” Somewhere in our brain, there is a mechanism that cuts the pear in half. We are only aware of the result of this decision: we have been spared the terms of this compromise.

We find a confrontation between sensory methods in the “height and weight” illusion or the Charpentier illusion (after the French physicist Augustin Charpentier who described it in 1891). In its simplest version, the volunteer is faced with two similar objects, for example two boxes, of distinctly different size but of the same weight. When asked to weigh them and say which one is heavier, he is definitely referring to the smaller one. This impression continues after the show and balance in support.

This illusion, which is not observed in young children without experience, is based on the fact that we have learned to anticipate the effort required to hold an object and that we unconsciously assess it by its size. Vincent Hayward, a professor at the Sorbonne University, explains. In the experiment, we overestimate the weight of a larger object, before holding it, which thus appears to be lighter. One day when I put this illusion on public display, a baker came to thank me explaining that all his life he wondered why the bread dough seemed lighter after it had risen…”

The conclusion of all these strange phenomena? Our senses are not physical instruments, Summarizes Vincent Hayward. All of our sensory machines generally do a good job. With little clues, she reconstructs a completely correct representation of the world. But sometimes the result is surprising to our conscience…” Weird but is he serious? Not only do these delusions have no harmful consequences, but one can also push the controversy even further, researcher insists. These defects in our nervous system, which are the counterpart to its efficiency, were chosen by evolution: they have allowed the survival of our species! ” Life retains innovations to adapt to its small imperfections.

By Pierre Vandegenste

“Organizer. Social media geek. General communicator. Bacon scholar. Proud pop culture trailblazer.”