A new look at the oldest Europeans

Our ancestors came to Europe about 45,000 years ago, but little is known about their fate and genetic affiliation. DNA analyzes of several early representatives of Homo sapiens, whose remains have been found in the Czech Republic and Bulgaria, now provide more information. The genomes of both sites give evidence of earlier Neanderthal crossings. While bits of early genetic material from Bulgaria can still be found in Asians today, populations of Homo sapiens from the Czech Republic have left no genetic traces in today’s Eurasia.

The time 45,000 years ago brought great turmoil to Europe: Neanderthals who lived in this region for thousands of years disappeared and were replaced by our ancestors: representatives of Homo sapiens who migrated from Africa to Eurasia via the Middle East. From analyzing the DNA of contemporary Europeans and Asians, we know that these early immigrants crossed several times with the last Neanderthals – which is why most Europeans today still carry one to two percent of Neanderthal’s DNA. But how the first representatives of Homo sapiens were distributed on the Eurasian continent and the extent to which their descendants contributed to today’s population is unclear due to the lack of fossils. “So far, only three genomes have been isolated from individuals who lived near the time when Europe and Asia were first settled more than 40,000 years ago,” Matija Hajdengak of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and colleagues explains. These include the roughly 45,000-year-old Siberian Ust’-Ishim, a nearly 40,000-year-old find from China and a roughly 40,000-year-old crater from Romania.

New DNA analyzes of many of the earliest representatives of Homo sapiens in Europe now offer new insights into the beginnings of European human history. The finds are the remains of three individuals from the Pachu Kiro cave in Bulgaria and the skull of a woman from Zlatikon in the Czech Republic. Two research teams – one headed by Hajdingak and the other headed by Kai Brover of the Max Planck Institute for Human History in Jena – have genetically examined these fossils and partially dated them. Scientists have paid special attention to the ratio and length of Neanderthal genetic sequences in the genome of these individuals, because this reveals when and how the ancestors of these early representatives of Homo sapiens crossed with Neanderthals. In addition, they compared the genome with the genome of contemporary Europeans and Asians as well as with the genomes of the first three known representatives of Homo sapiens in Eurasia.

Pachu Kiro: Ancestors of Neanderthals and Asian Relatives

Analyzes of discoveries from the Bach Kiro Cave confirmed that three of these individuals lived from 45,930 to 42,580 years ago. This makes you one of the oldest known Europeans. Genetic comparisons also showed that these early representatives of Homo sapiens in Europe carried between 3.0 and 3.8 percent of Neanderthal DNA in their genome. From the length of the individual Neanderthal genes segments, the researchers concluded that the ancestors of the three individuals must have interbreed with Neanderthals. These husbands were only from six to seven generations, Hajdengak and her team reported. Scientists say: “This indicates that the mixing of Neanderthals and the first modern humans who arrived in Europe occurred more frequently than is often assumed.”

DNA comparisons with other populations showed little agreement with the distinct gene segments of Europeans today: “The three individuals share more alleles with today’s populations from East Asia, Central Asia and the American continent than western Eurasians do,” says Hajdengak and her team. . The discovery of early human Homo sapiens from China also shows similarities to the three genomes examined from Bulgaria. The researchers concluded that the immigrant population, who belonged to them from the Bachu Kiro Cave, arrived in Europe, but then moved to Asia. Their descendants were expelled in Europe by representatives of Homo sapiens who later emigrated, and their genetic makeup disappeared from the European gene pool.

Kon Zlate: The oldest European?

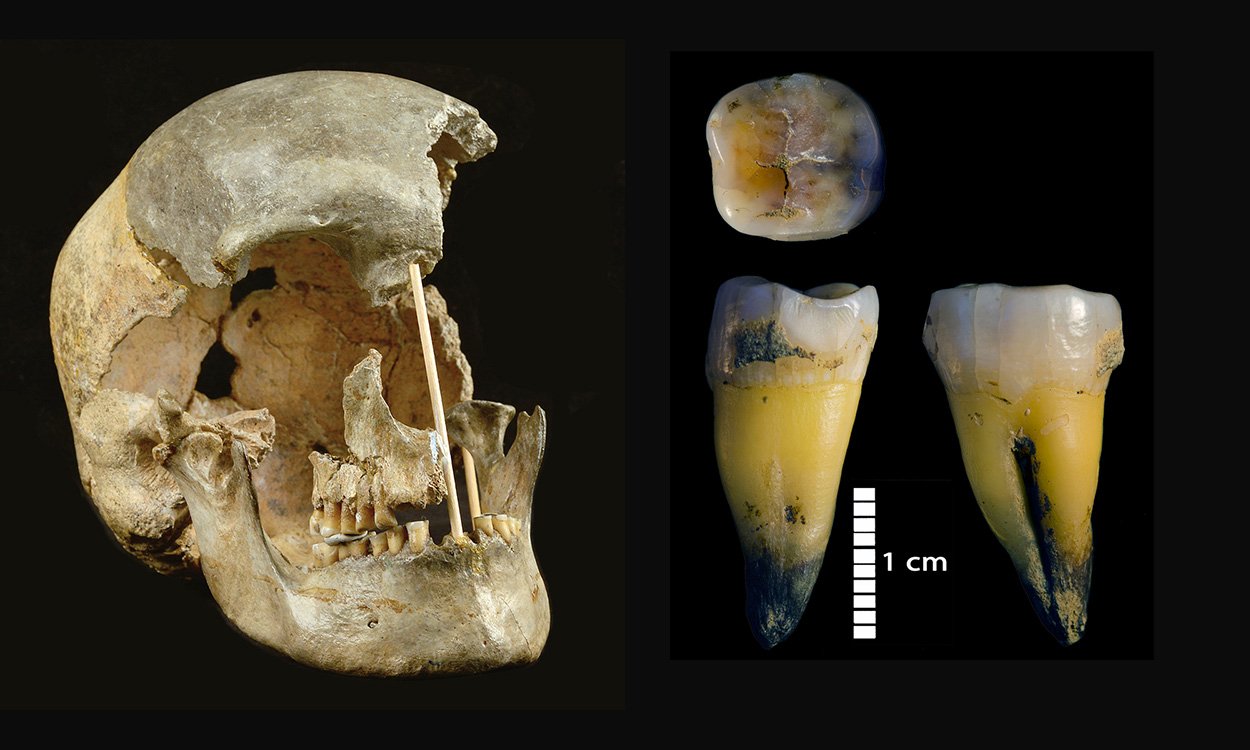

The second research team led by Prüfer devoted its analysis to the skull of a Homo sapiens woman from the Zlaty kun site in the Czech Republic. The age of this fossil was previously unclear because stone tools in the cave itself could not be assigned to any known cultural stage, and radiocarbon dating produced contradictory results – the range ranged from 15,000 to 27,000 years. As the team has now discovered, these relatively low age values can be attributed to post-discovery contamination: “We found evidence of bovine DNA contamination, indicating that parts of the skull were bound together with animal material. Adhesive material in the past.”, Explains co-author Cosimo Posth from the University of Tübingen. He and his colleagues found evidence of the true age of this woman Homo sapiens in her genome. Because she also possessed long, unbroken sections of Neanderthal DNA in her genetic makeup. “Zlate-kun holds longer slices on average than all other Eurasian hunters and gatherers so far examined,” the team says. The proportion of Neanderthal DNA was also high, at 3.2%.

From this, the researchers concluded that this woman must also come from the beginnings of the colonization of Eurasia by Homo sapiens. “Our results indicate that slate being the same age as an individual from Ust Ishim, and possibly a few hundred years older,” Brover and colleagues wrote. “Thus Zlaty kun could be the oldest European human fossil with a preserved skull.” But unlike her nearly genetically different contemporaries from the Bulgarian cave, there is no connection between this woman and her inhabitants with the Europeans or Asians who live today. According to the research team, this indicates that this group of early migrants did not appear to be able to establish itself in Europe.

“It is very exciting that the first humans in Europe did not succeed in the end,” says senior author Johannes Krause of the MPI Institute for Human History. “As with Ust ‘Ishim and the Skull from Oasis 1, the Zlaty kun also does not show genetic continuity with modern humans who lived in Europe less than 40,000 years ago.” A possible, albeit highly speculative, explanation for this failure According to the researchers, one of the first attempts to migrate Homo sapiens could have been an eruption of a massive volcano under the Phlegian fields in Italy about 39,000 years ago. Scientists speculate that “this volcanic eruption severely affected the climate of the northern hemisphere and could reduce the chances of survival of Neanderthals and early modern humans in large parts of western Eurasia.”

Source: Matija Hajdingak (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig) and others, Nature, Doi: 10.1038 / s41586-021-03335-3; Kay Brover (Max Planck Institute for Human History, Jena) and others, Ecology / Evolution, Doi: 10.1038 / s41559-021-01443-x

“Organizer. Social media geek. General communicator. Bacon scholar. Proud pop culture trailblazer.”